An aerial view of Papunya, Northern Territory, Australia shows a vast expanse of red earth, etched with concentric circles and semi-circular dirt tracks. Beneath the ochre earth, millions of honey ants travel between a complex network of underground chambers. The two are, of course, connected. Upon consultation with community on the design of the settlement, town planner Reverend JH Downing was handed a painting of Tjala Tjukurpa (Honey Ant Dreaming), which informed today’s satellite view. Located on the Tropic of Capricorn, 240km northwest of Alice Springs, Papunya is remote to any urban centre but has long been occupied for its proximity to a major Tjala Tjukurpa site. It has also, more recently, been sanctified by contemporary art appreciators as the birthplace of the Western Desert Art Movement.

In the winter of 1971, a group of fewer than 30 Papunya artists began painting their traditional Dreaming patterns using Masonite boards given to them by art teacher Geoffrey Barden soon after his arrival in the settlement. He would later become affectionately known as ‘Mr Patterns’ by the artists and has since been recognised for facilitating the incredible artistic output of the early days. By the end of 1972 approximately 1,000 small panels had been painted by a core group of senior initiated lawmen. In the process, a radically new art form had been instituted; this has now become understood as the watershed moment of the Western Desert Art Movement.

Despite initial market indifference, the artists persisted with the encouragement of art teacher Geoffrey Barden. By the end of the decade the group had been joined by 20 artists who painted regularly with Papunya Tula artists. At the time, few others were prepared to commit their Dreamings to canvas. From this discursive tradition, the paintings began their long trajectory of circulation and recognition, ultimately arriving at cultural centres across the country and internationally. Painting has since become among the most enduring media through which these communities have made their presence known.

By the time the ’80s rolled around, the Papunya Tula Art Centre was financially sound and able to support and encourage the development of new artists. The period saw unprecedented artistic activity across the entire Western Desert, and the number of painters on the books at Papunya Tula swelled to almost 100 by the beginning of the ’90s. On a visit to the region, Andrew Pekarik of the New York Asia Society noted that there must have been more artists per head of the population in the area than anywhere else in the world outside of the Latin Quarter. The region would soon far exceed its Parisian counterpart, as painting became popular throughout the neighbouring areas.

In Yuendumu, 100km north of Papunya, Warlukurlangu Artist Association was formed in 1985. Napperby and Mt Allan followed. In 1988 the movement became emphatically “fine art” with Dreamings: The Art of Aboriginal Australia, a highly publicised exhibition at The Asia Society Gallery in New York. By 1997, the tectonic social and cultural movement was internationally sanctioned when Western Desert artists Emily Kame Kngwarreye and Yvonne Koolmatrie represented Australia at the Venice Biennale alongside Indigenous Queensland artist Judy Watson.

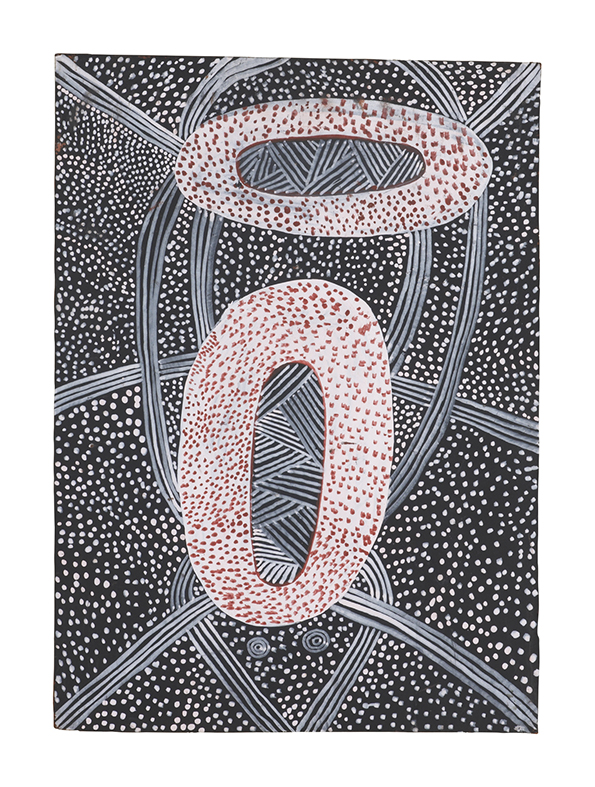

In the ’70s and ’80s, Western Desert art was synonymous with the ‘dot painting’ initiated by Papunya Tula artists. These trademark dots are no longer characteristic of all of the work being produced in the region, and also describe work produced elsewhere. The area of the ‘Western Desert’ refers to a cultural and linguistic demarcation, not a geographical one; and while the broad-brush description gives the impression of homogeneity, the region boasts a rich diversity of language, ritual, and spiritual beliefs.

“It’s kind of like the UN,” says Luke Scholes, Curator of Aboriginal Art at the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT). “There are many linguistic and cultural groups that occupy a vast stretch of country with no defined borders and historical differences in complete, coinciding and shifting ownership of various places.” Though the social reality is far more fluid than the neat conceptual compartment of the ‘Western Desert’, the emergent art-historical term broadly describes a school of painters from the Central Desert and adjacent regions. The works emerge from a way of life and a set of practices that have changed and continue to evolve and inform and shape social life in the region.

Claire Summers has witnessed the ever-changing modes of practice across the region as Executive Director of Darwin Aboriginal Art Fair Foundation (DAAFF). The fair has become an annual meeting point for art centres from across the country to gather in a celebration of Indigenous art. “No community is the same,” she tells me. “Each has their own story of colonialism, and through community ownership of Indigenous art centres we see a diverse connection to lore and Country. These different narratives create distinct styles.” Take, for example, the artwork of Warakurna artists such as Eunice Yunurupa Porter, Judith Yinyika Chambers and Dianne Ungukalpi Golding. Established in 2005 and located 300km west of Uluru, the artists of Warakurna have become known for incorporating familiar Western Desert symbols and dots into a figurative style that recounts everyday life, as well as historical and contemporary stories. For this community, the early Papunya paintings were seen as too explicit in their renditions of ceremonial objects and scenes.

Scholes, who confesses to thinking about Western Desert Art “too much”, argues this figuration existed in the early years of Papunya painting prior to the efflorescence of movement in the ’90s. “Figuration of animals, snakes and birds do appear in various forms in early desert art but went away.” Though the curator acknowledges Barden’s role in helping to facilitate the early stages of Papunya’s growth, he believes Barden’s push for the artists to evade ‘whitefella stuff ’ “stifled such figuration”.

“With the boom of the ’90s led by artists like Turkey Tolson Tjupurrula working in esoteric, minimal and seemingly abstract kind of paintings, the idea of Aboriginal art became a circle and line composition with U-shapes and L-shapes,” Scholes continues. “This iconography swept in but there was really a passage of figuration prior to that boom. What we see now is a re-emergence of figuration more than anything.”

In 2017, together with Sid Anderson, Long Jack Phillipus Tjakamarra, Michael Nelson Jagamarra AM, Joseph Jurrah Tjapaltjarri and Bobby West Tjupurrula, Scholes co-curated a landmark exhibition at MAGNT, Tjungunutja: from having come together, which delivered a thorough interpretation of the confluence that produced this art movement. The exhibition negated the modernist myth that it was rooted in a single place, time and person (namely Barden) and was instead a result of dynamic, multifactorial beginnings. Rather than instigating the movement, Barden was one among several non-Indigenous supporters who arrived in a place where a cross-section of different communities had been aggregated by colonisation and assimilation policies. The exhibition and supporting essays acknowledged the dawn of self-determination under the Whitlam Government, which set a new tone for intercultural exchanges and interactions with government bureaucracy. The engagement with popular culture such as comic books and American cowboy films was also noted. All were important in forming fertile ground for the cultural assertion of Dreaming and ceremony across the region.

When Papunya Tula artists began committing their cultural worlds to canvas, well-established centres for art and craft such as Ernabella Arts followed suit. Located in Pukatja on the APY Lands on the eastern end of the Musgrave ranges in the far northwest of South Australia, Ernabella Arts is touted as Australia’s longest-running Art Centre. VAULT spoke to the senior directors of Ernabella Arts, Tjunkaya Tapaya and Alison Milyika Carroll, who explained the genesis and ever-changing artistic influences of their mode of practice.

“Women have always told stories in the sand, Dreaming stories and working out problems. In the mission times, we began to tell those dreams and stories with chalk on paper, until it became a craft centre for women,” says Tjunkaya Tapaya. “From there we made Christmas cards, and wall hangings before we used batiks.” On travels to Japan and Indonesia in the ’70s, senior women learnt batik and printmaking techniques and brought them home. The centre became famous for its batiks and spread the artists’ learnings to the regions of Utopia and Fregon. “We made lots of things, like batik, before moving onto canvas – and then we started to tell Tjukurpa law and culture instead of just doing design-based pieces,” Tapaya adds. Art is a heartbeat of the community: more than half of the populace of around 500 create at least one work of art at the centre during the course of a year across a wide variety of media including ceramics, batiks, Tjanpi (weavings) and painting.

Education in the inherited visual language of the Dreaming designs is a passage to adulthood in the Western Desert culture that creates the potential for everyone to take up the vocation. “It does not seem to matter how indifferent the artist’s past performance nor how prolific or sparse their previous output, nor their age or years of experience,” wrote Vivien Johnson in her seminal text Aboriginal Artists of the Western Desert: A Biographical Dictionary. “The power of cultural practices within Aboriginal society dating back millennia from which Western Desert artists draw their inspiration, seems the only possible explanation of their ability to confound the expectations of art audiences by continually turning up with astounding new paintings.” It is no surprise, then, that this year’s $100,000 Hadley’s Art Prize was awarded to Papunya local Carbiene McDonald Tjangala just a year after the artist first picked up a paintbrush.

The Aboriginal representation of landscape has eclipsed the Western tradition of landscape painting as the leading form of expressing relations to place in Australia. The Wynne Prize, which is awarded annually by the Art Gallery of New South Wales for “the best landscape painting of Australian scenery in oils or watercolours or for the best example of figure sculpture by Australian artists”, has been dominated by painters from the region for the past decade. The winning works are also testament to the ever-changing visual expressions from the region. Executed by the Ken Family on an enormous canvas, the 2016 winner Seven Sisters consists of different songlines and the honey ant dreaming site rendered in a richly coloured network of dots and zigzagging lines, making it vastly different from the origins of a category it still technically falls under.

Despite the circulation of Western Desert Art throughout public institutions globally since the ’80s, it was a recent endorsement of the movement by American comedian and actor Steve Martin that alerted megadealer Larry Gagosian to such work. A voracious art collector, Martin has been preoccupied with the movement since sighting (and immediately acquiring) the work of Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri in New York in the summer of 2015. Today at his home in the Upper West Side, works by Venice Biennale exhibitor Emily Kame Kngwarreye and Wynne Prize awardee Yukultji Napangati hang alongside Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and David Hockney.

Notwithstanding the New York art world’s knee-jerk reaction to view the work through a Western framework, the gallery insists that “Despite evident resonances with mainstream abstraction, Indigenous Australian art emerges from a fundamentally different line of inquiry.” Though none of the works in Martin’s collection were for sale across two successive showcases in the New York and LA outposts of the gallery, the entrance of the museum-quality historical works into the apex of the contemporary art world will not only upsurge their commercial value in what has been termed ‘The Gagosian Effect’, but is also an overdue recognition of the luminous movement.

Though the early Papunya boards have long been considered the purest iteration of Western Desert art, they culminated from a complex set of outside influencing factors. The categorisation itself arises from an attempt to understand a region of diverse languages and spiritual practices that continue to find expression in distinct visual languages. Even centres like Ernabella Arts, which require a permit to reach, are not immune to outside influences such as market demands or the more positive introduction of new media. They also continue to change from within with the inheritance of new songlines and contemporary concerns.

When VAULT spoke to director Tjunkaya Tapaya, for example, she was in the process of creating a work about the trees in the surrounding area, out of a concern that younger generations were losing the traditional language to describe different species. Even as the styles of the Western Desert devolve from the original line-and-dot iconography devised in the 1971 Men’s Painting Room in Papunya, the duality of a firm grounding in tradition and sustained nonIndigenous influences remain.