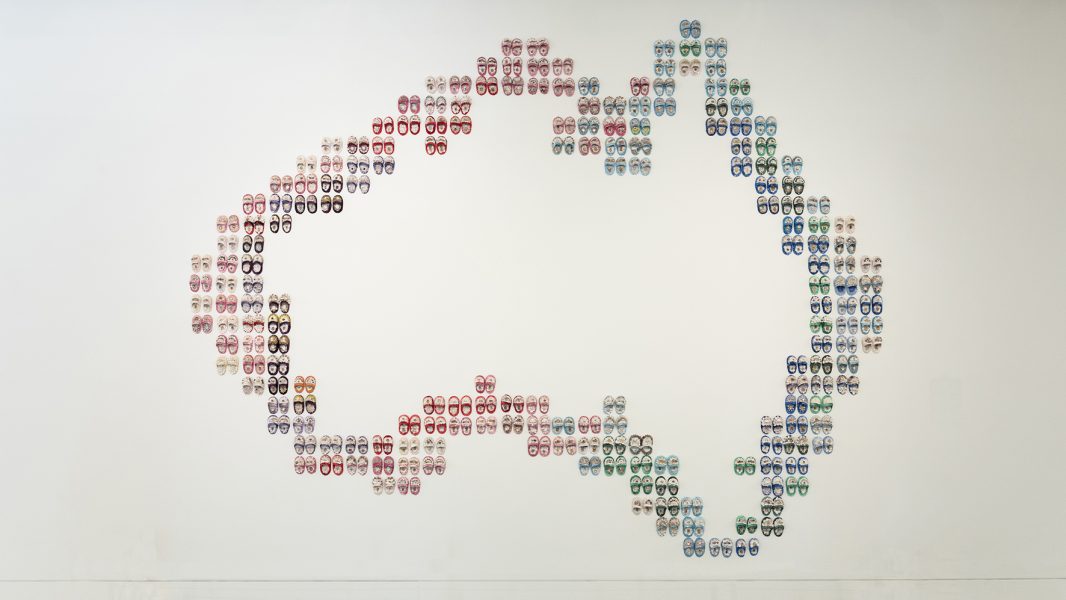

On entering the group show RocoColonial one is struck first by the work of Bidjigal artist Esme Timbery. Tracing the outlines of the nation, the work is an empty map of Australia made from baby slippers adorned with many tiny shells gathered from South Coast beaches. Each pair of shoes is a memento mori for the Aboriginal children taken from their families in the 19th and 20th centuries by church and state. A homage to the Stolen Generation, the installation observes the impact of British colonisation on Aboriginal people. Commissioned originally by Campbelltown Arts Centre, the 2008 work is usually arranged in a rectangular shape, but in this context it is a distinctly Indigenous rococo cartouche and an apt starting point for a show that explores the overlap of the rococo tradition and colonialism in a contemporary Australian context.

The term rococo is derived from the French term rocaille used to describe the use of seashells, pebbles, and glass bonded with mastic or cement to decorate grottoes or fountains. The movement, which originated in France, was later associated with an ornate decorative style that unified art and design for the first time the 1700s. In 1770 as Cook charted the east coast of Australia, the end of the rococo period was marked by the marriage of its leading figure, Marie Antoinette, to Louis XVI of France.

The horror vacui, a term used to describe the horror of untouched surfaces, of Timery’s colonised landscape is antagonised by the lush installation by Renjie Teoh that faces it, at the show’s point of entry. Designer Marc Newson’s Orgone Lounge, 1989, a jade-coloured chaise lounge rendered in fibreglass, is set against an opulent backdrop reminiscent of aristocratic interiors and it sits at the centre of an oyster-shaped cartouche. The works are emblematic of two disparate periods that happened successively on opposite sides of the world.

It is the deftly-crafted dialogue between the works of 15 artists in the exhibition that reveal the connections between the two wildly different, but similarly slippery, concepts of rococo and colonialism. Tècha Noble’s Whispering Heads, a gang of extravagantly wigged helmets, look on Jennifer Leahy’s photographic series The Deep Surface in which white-gloved female hands hold earthen precious gems. Both point to the pursuit of beauty and power. Noble’s figures are a droll take on the obsession with wigs, which were synonymous with status during the rococo period. Leahy’s series re-enacts the dispossession of land and its resources by colonisers enamoured with European fashion at the time.

Justin Shoulder’s punk-tech, dimly lit humanoid-android figure, Lolo Ex Machina, looms opposite. Looking on from both sides are the faces of Tony Clark’s painted portraits of hypothetical jewellery designs and mannequins dressed in lavishly beaded bird costumes, Chimera and Galah, in an installation by Noble and Australian designers Romance Was Born. Clark’s nod to classicism and the pageantry of dress in Chimera and Galah, and Lolo Ex Machina, point to the rococo mode of life as spectacle.

Scholarly approaches to the rococo era have revealed the extravagance of the time as a veneer to a deep anxiety of impending misfortune, which in this context can be seen in Sunday BBQ, BYO, a single-channel video work by Joan Ross. This piece is another critical reference point in the show. In a witty depiction of the Australian BBQ ritual, Ross reworks the images of convict painter Joseph Lycett to subvert the triumph and reveal the unnerving realities of colonisation. The faces of Indigenous figures are obscured, the landscape wobbles and the flag of night-sky stars that flew when the white men arrived erupts in gunshots and bloody fireworks.

Hazelhurst Arts Centre was chosen as the first stop on the RocoColonial tour for its close proximity to the site of Cook’s landing. Through a blaze of colour and a panoply of media, artistic organiser Gary Carsley manages to sync the concepts of rococo and colonisation and in doing so, connects Australia’s past with a wider-global historical narrative.