In the final lot of a Sotheby’s evening sale in October last year, Banksy’s work shredded itself after being sold for USD$1.4 million. After all the media hype that ensued, the work was valued at least 50% more. The moral of the story: the art market always wins.

And it remains a barometer of cultural change. The 2018 season saw the first piece of AI-generated art, a portrait, sold at auction, the use of blockchain for payment, and – more importantly –a new high watermark for a living African-American artist, Kerry James Marshall. The artist quadrupled his own personal record with the May 2018 Sotheby’s sale of Past Times (1997), for USD$21.1 million to record executive and entrepreneur Sean Combs (best known as P Diddy or Puff Daddy). This result demonstrated that the historical value and price point of African-American artists might now be levelling with their white peers. Marshall was quick to comment, “This is probably the first instance in the history of the art world where a Black person took part in a capital competition and won,” and as New York art dealer and advisor Todd Levine noted, it “signalled an intensification of activity among African-American collectors.”

No longer just a domain for Abstract Expressionists, the auction world is clearly playing catch-up with broader cultural conversations. The record sale is testament to the importance and centrality of Kerry James Marshall, confirming the success of his endeavour to insert Blackness into the narrative of contemporary art. “The overarching principle is still to move the Black figure from the periphery to the centre,” Marshall tells curator Dieter Roelstraete of his practice, in an interview presented in Kerry James Marshall: Painting and Other Stuff, “and, secondly, to have these figures operate in a wide range of historical genres and stylistic modes culled from the history of painting. Those really are my two overarching conceptual motivations. I am using African-American cultural and social history as a catalyst for what kind of pictures to make. What I’m trying to do in my work is address Absence with a capital A.” The absence/presence of the Black figure in Western art is damaging in that it marginalises Black viewers and leaves no referents for collective memory and identity-building.

As with all of his works, the ambition of Past Times is explicit: to paint a grand epic narrative that included Black figures. Recalling historical works such as Georges Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884–86) and Edouard Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’Herbe (1862), the monumental painting, measuring 280 x 396 cm, is set in a lakeside Chicago park, depicting Black suburbanites engaging in various leisurely activities associated with the white and wealthy: golf, croquet, picnicking and water-skiing. Three of the figures stare quizzically back at the viewer, pausing for a moment. What is most striking about it, and common in all of Marshall’s paintings since 1980, is the uniform, flat, velvety blackness of his figures’ skin. The effect is rendered using three types of black paint – carbon black, Ivory Black and Mars Black – underpinned by yellow ochre, raw umber and two shades of blue to give him seven blacks to work with. It is these undertones that reveal nuances of warmth and variations of hue. Not a drop of white is mixed in the flesh. This is a conceptual underpinning and rhetorical play on the broad brush of the word ‘Black’ used to describe the many shades of real- life ‘blackness’. It addresses the invisibility of Blacks from the canon yet paradoxically makes them more visible against the bright greens and vivid blues of the backdrop. An important part of Marshall’s creative fingerprint, this unmediated shade is “a response to the tendency in the culture to privilege lightness. The lighter the skin, the more acceptable you are. The darker the skin, the more marginalised you become. I want to demonstrate that you can produce beauty in the context of a figure that has

that kind of blackness.”

The artist isn’t irreverent of the historical art canon; in fact, he is fluent in its technical vocabulary. Marshall does not correct or critique tradition, but instead expands on it by asserting new representations of African-American identity and disabusing the all-white delusion that exists in studies of art. For example, for Untitled (Underpainting)

(2018), from his most recent showing at David Zwirner gallery in London, Marshall adopted a technique frequently employed by Renaissance masters: underpainting using a base of burnt umber paint, so that the end product emits a luminous glow. The piece depicts a salon-style museum in which two groups of Black students learn about art in the same way on different sides of a wall. Here, he acknowledges the role of museums as repositories of art history, but questions the place of Black bodies while assuming the role of an ‘Old Master’ himself. “All my life I’ve been expected to acknowledge the power and beauty of pictures made by white artists that only have other white people in them; I think it’s only reasonable to ask other people to do the same vis-a-vis paintings that only have Black figures in them,” he tells Roelstraete. His obsessions with learning the techniques of his predecessors relates to his allergy to “dependency”. Time and again, Marshall stresses the need to be as good or better: “The lack of mastery makes you vulnerable.” Once you understand how to be on the same level as venerated artists, “You can shape the world you want.” The artist’s technical acuity gives him agency to recode art history in a manner he sees fit.

After 35 years of committing himself to creating an inclusive ‘counter-archive’, Marshall’s work became embedded in art history with Mastry, a blockbuster multi-venue retrospective held from 2016–17. Across 72 works, his Black figures populated the walls of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, New York’s Met Breuer and MOCA, Los Angeles. The show was all the more poignant in that it was staged during the throes of a political race that saw unashamed racism rear its ugly head across the US, emboldened by the campaign of President-elect Donald Trump.

For Marshall, the political campaign was just one of many personal experiences of seismic cultural change in contemporary American and Black history. Born in 1955 in Birmingham, Alabama, the artist moved to South Central Los Angeles as a young boy, where his life was marred by frequent violence on the battleground of the Black Power movement. As the Black Panthers stirred, so too did the Black Arts Movement – a group of politically motivated black poets, artists and writers who still inform Marshall’s practice. Though Marshall’s work is inseparable from his political impulses, his ambitions remain neatly in the art-historical arena. For example, his works are often simple narratives of African-Americans going about their everyday lives. His images generally aren’t event-filled or about political activism. The first of his family to attend college, Marshall earned his BFA from the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles in 1978.

By the late ’80s, he was exhibiting throughout Europe and the US and in 1999, he earned an honorary doctorate from his alma mater. In addition to the major retrospective, Mastry, during 2018 the artist also presented Kerry James Marshall: Collected Works at the Rennie Museum in Vancouver and Kerry James Marshall: Works on Paper at The Cleveland Museum of Art. Best known for his paintings, Marshall also works across a panoply of media including sculpture, photography and installations. Last year, he was commissioned for a site-specific public commission called A Monumental Journey in Des Moines, Iowa.

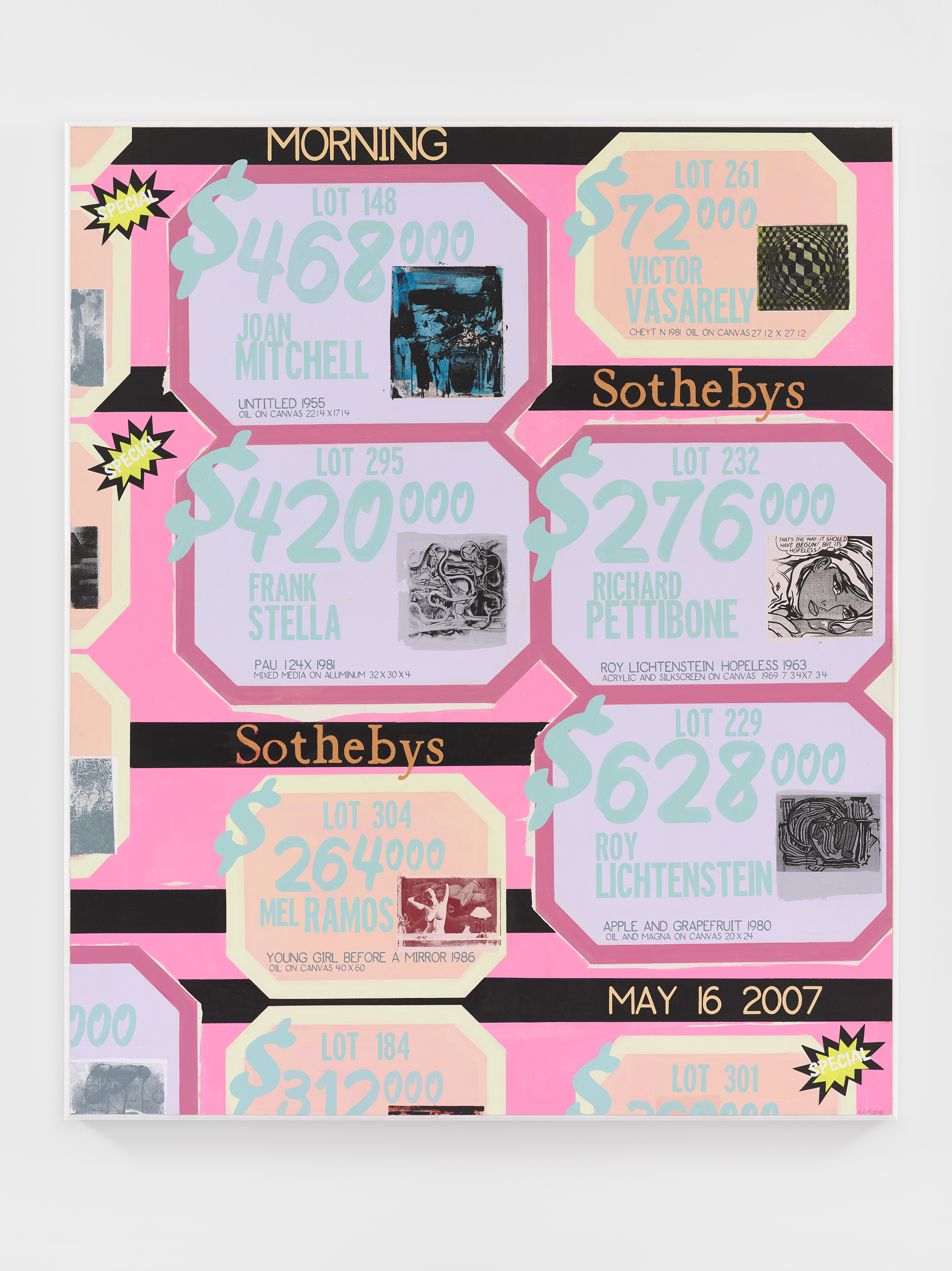

After Mastry, Marshall’s commercial show, satirically titled History of Painting, was held in October last year at the London outpost of David Zwirner’s eponymous gallery. He told Angela Choon of the gallery, “You could make an argument that it is a grand, arrogant claim to address the history of painting. On another level it’s a way of setting yourself up for failure, because the scope of the show suggests something so large – but it seems to me the only way forward…” The show featured landscape, still life, portraiture, abstraction, and history painting. Among the works was a tongue-in-cheek series of paintings that shares its title with the exhibition. In a comment on the commodification of artwork, artist names are depicted next to the corresponding auction prices in the style of a supermarket circular. The work was made a decade before his own newsworthy auction results and engages with how value is created and assigned to artwork.

In 2017, Time magazine listed Marshall as one of the year’s most influential people. In 2018, Marshall came second in the ArtReview ‘Power 100’ list, topped by none other than his own gallerist David Zwirner. Tamsen Greene, Director of Jack Shainman Gallery of New York which has been showing the artist since 1982, told VAULT decidedly, “It’s not an exaggeration to say that Kerry James Marshall is one of, or perhaps the most, significant voices of his generation.” Though the auction result is what made headlines, the sweetest success for Marshall is his mutual benediction of and from museums. As the racial demagoguery of Trump’s America remains the backdrop to his work, Marshall’s endeavour to expand collective identity for those long marginalised becomes even more important. African-Americans rely more on the steady conviction of artists like Marshall to buoy their idea of what is possible and make sense of moments theory cannot grasp.